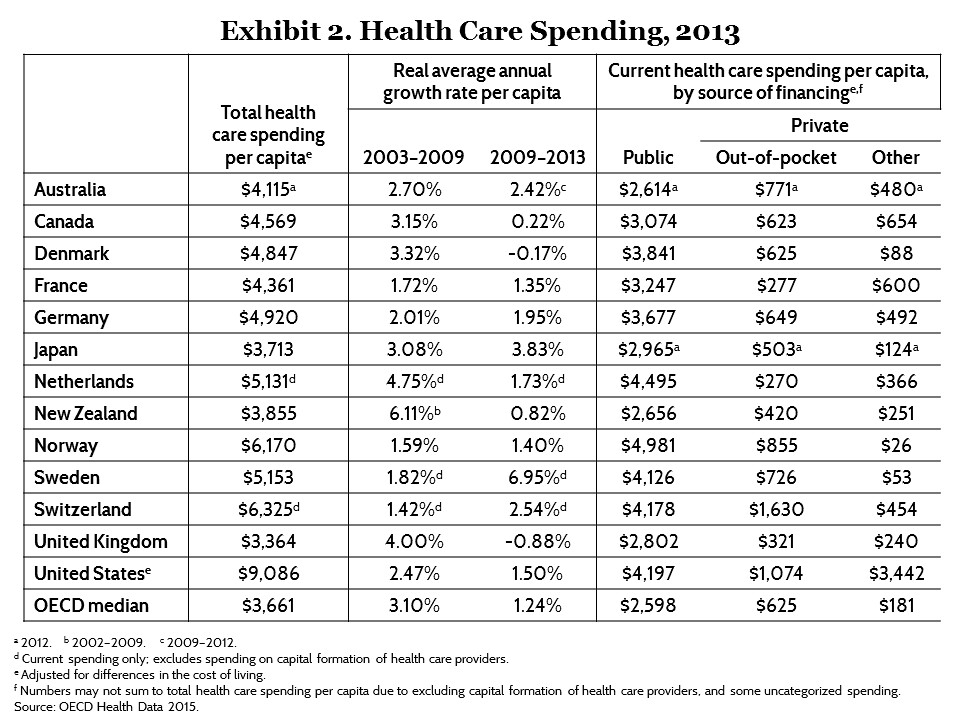

Despite some belief to the contrary, the U.S. has one of the best healthcare systems in the world. The United states has on average a higher survival rate for most major diseases, higher access to care, more treatment options, shorter waiting times, and more spending per citizen than the majority of countries in the world. The United States' healthcare system has one of the highest survival rates in the world, and is far higher than most other comparable first world countries, with a hospital survival rate 45% higher than in the UK on average, according data by the UK's own NHS system (from the work of Professor Sir Brian Jarman, with the raw data being here.) [1][2][3][4][5] In terms of overall hospital mortality rates, the U.S. is consistently in the top 10 lowest, which while not measuring healthcare capabilities directly, is a rough indicator of quality of care. [6] For example, the mortality rate for Cardiovascular disease is 5.5 per 100 patients in the U.S., only marginally worse than Australia (4.4), New Zealand (4.5), Norway (4.5), and Sweden (4.5), while being 40% lower than in the UK (7.8), and 50-60% lower than Spain (8.5) and Luxembourg (8.8), and Germany (8.9). When looking at Ischemic Stroke, the U.S. had a mortality rate of 4.3 vs. Japan (3.0), South Korea (3.4), Denmark (3.5), Norway (5.3) and Finland (5.4), while being 55% better than Germany (6.7), and Switzerland (7.0), 70% better than Iceland (7.4), and the Netherlands (7.5), twice as effective as France (8.5), and 2.4 times more effective than the UK (10.2). As these are the leading causes of death in first world countries, making up over 45% of deaths or more in the aggregate, they show a general representation of quality of the healthcare system overall. Many other studies, not only from the U.S. but from other country's government's, such as the British NHS system, agree on the general quality of the rest of the world and the U.S. health care, and the fact that the U.S. provides some of the best healthcare services and invents the majority of the world's cure and treatments, is commonly accepted by most medical professionals. Sweden, Switzerland, Norway, and Denmark have similar medicare and medicaid systems, based on the U.S. system, copying much of the written law of these systems and incorporating them in to their own systems, with the U.S. already having similar systems and outcomes to them. This is not all just from private care; the U.S. government spends more money per citizen than any other country in the world when direct and indirect spending is considered, and is in the top 5 when direct spending by the government on it's citizens is considered, with 4,197 dollars per person directly from the U.S. government, and 3,442 from indirect government-mandated health insurance (largely from government-mandated health insurance), for a combined total of 7,619 dollars. In comparison on direct spending levels, the UK government spends 2802 dollars per citizen (far less than the U.S. at 4,197), Japan 2965, Denmark 3841, France 3247, Australia 2614, and Canada 3074 per person. The U.S. outspends Canada, France, the UK, and virtually every major country in the world by a wide margin, and has a higher survival rate for it's citizens, as much as 20-40% higher. In regards to direct spending, the Netherlands (4,495 - 4,197) and Norway (4,981 - 4,197) outspend the U.S. slightly, with Switzerland having roughly comparable spending levels (4,178 - 4,197), with each country also having roughly comparable survival rates for most diseases. However, most of these countries have more money per capita than the U.S. (although exact figures vary), between 1.5 to 2 times as much money per citizen, and so for the U.S. to be spending nearly as much as them or more when indirect spending is counted on healthcare, is rather impressive feat in it's own right. Proportionate to our wealth and in total numbers, we have among the highest government spending in the world, and depending on the figure far more than any other country in the world.

The percentage of spending by the government itself in the U.S. has also risen, consistently having around half of all healthcare paid for by the government (and another large amount mandated by the government via government-mandated health insurance). It has approximately a 24-30 minute waiting period in emergency rooms, vs. 8.8 hours in Canada, 9 hours in the UK, and is much faster and with better results than most countries in the world. Patients in Canada waited an average of 19.8 weeks to receive treatment, regardless of whether they were able to see a specialist or not. In the U.S. the average wait time for a first-time appointment is 24 days (~3 times shorter than in Canada); wait times for Emergency Room (ER) services averaged 24 minutes (more than 4x faster than in Canada); while wait times for specialists averaged between 3—6.4 weeks (over 6x faster than in Canada). [1][2][3] The government provides healthcare to those at or 33% above the poverty line, and for all emergency care, which means it won't leave people to die if they need emergency treatment, with the bill for this passed by the Republican President Ronald Reagan. Other people who receive government funding are the elderly (people over 65), children (people under 18 ), the seriously injured, disabled people, military veterans, and more, such such as those with life threatening diseases such as cancer or those that qualify as having a disability such as the majority of people with diabetes [1]. Not all people in the U.S. receive government funded healthcare, but virtually all those in need do as well, meaning it is not only relegated to the rich or elite class of people. The percentage of people with access to healthcare is among the highest in the world as well, meaning very few people are left out of the system. and by the WHO definition the U.S. already has universal healthcare. This means that we have more spending per person, higher quality of care per person, and yet roughly the same amount of being treated in total, with the entire system also operating more quickly than many of it's peers, implying we do not actually leave the poor or disabled to fend for themselves, and that there are no serious burdens for the average citizen when it comes to access to healthcare.

Despite this, many believe that the U.S.'s healthcare system is terrible, among the worst in the world, and specifically because of conservatives or private healthcare; there is a rather prevalent idea that we need to copy Norway and other such supposedly socialist countries (who are not socialist and have a similar system to the U.S., with a similar healthcare quality to the U.S.), who in their minds have better healthcare systems, a common sentiment shared by individuals such as Bernie Sanders. Arguments against the U.S. healthcare system rarely have to do with the quality of care itself, and often ignore the high coverage rates and good treatment of the poor the U.S. actually has. Instead arguments focus on peripheral issues, such as the chance of getting certain types of diseases, such as heart disease or cancer, or the slightly lower life expectancy than some countries (with a life expectancy or age-of-death average of 79 in the U.S., in comparison to 83 in Japan, which has the highest life expectancy in the world). While the U.S.'s healthcare system is objectively better than most other countries in the world by most metrics, the U.S. does have a slightly lower life expectancy, and a higher rate of cancer and heart disease than many other countries, mostly stemming from obesity, fast food, sedentary exercise-free lifestyles, genetics, and drug use, such as cigarettes and illegal narcotics. Cigarettes kill approximately 480,000 people per year in the U.S. out of 2.6 million total deaths or roughly 20% of all of those who die, despite chronic smokers making up 5% of the U.S. population, and hundreds of thousands more die from other drugs, such as Opiods and alcohol. The U.S. has health problems, but not a problem with it's healthcare system, which means the U.S. as a collective whole needs to change it's diet and lifestyle, and not the healthcare system per say. The primary issue is in judging the health care system erroneously by how many people die of a particular disease as a whole, rather than how well the system is able to treat those diseases once people have them. The price of a free country is obesity from fast food and health problems from smoking, and thus while people need to have these freedoms, they should also be encouraged culturally not to abuse them.

The primary issue with single payer systems, of which Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Norway, and Finland do not actually have, and the UK and Canada do have which have comparably lower survival rates for most diseases, is they are generally overloaded. The largest cost of healthcare in most countries is Administration and Labor, with drug costs being approximately 10% in the U.S., for example. [1] The only way to cut costs in most systems is to cut workers, be it by numbers or their salaries, and this leads to a less effective system overall. In a finite system with finite resources, it becomes imperative to ration, and thus wait times are extended dramatically when healthcare workers are overloaded with cases. In systems where there are more healthcare practitioners, the workers work work less hours, and are better paid, they generally perform better, having more downtime and less exhaustion in the very demanding environment of healthcare where they try to save lives, which necessitates long periods off work, which is why systems such as Denmark, the U.S., and most Scandinavian countries which do spend more money tend to do better than those which spend less money, such as the UK. The UK for example struggles to hold on to doctors who feel exhausted and hopeless, receiving very little pay despite having expensive degrees, and their healthcare system suffers because of it. [1][2][3][4] Less healthcare practitioners, who are also fatigued from being overworked, and less motivated due to the poor pay, leads to longer waiting times as the staff becomes overloaded, such as the UK or Canada's emergency wait times being nearly 9 hours vs. 30 minutes for the U.S., leading to higher death rates. Having a more robust and better financed healthcare system tends to improve survival results, and creating as cheap a system as possible tends to severely impact it's ability to function.

Fundamental causes of health problems (Obesity and Drug use)

Life expectancy, your chance of dying from a disease, and many other factors are not determined by how good of health services you receive, but rather by external causes such as genetics, diet, and environment. There is currently no pill a doctor can prescribe that will prevent people from overeating, or making lifestyle choices which may negatively effect their health, such as drug use. These changes must be determined by a shift in culture, and through education on how to avoid these health problems. The U.S. has a much higher rate of obesity and drug use than the rest of the world, especially other developed countries (Page 5). Out of all OECD countries the U.S. has the highest obesity rate, only slightly below Mexico in some earlier studies (although as of 2015 the U.S. still appears to be higher), and far above the rest of the world and other developed countries. 38.2% of Americans are obese, vs. 26.9% in the UK, with Iceland at (19)%, Japan (3.7)%, Italy (9.8 )%, and France at (15.3%), for example as of 2015. Not surprisingly, Japan has the highest life expectancy in the world and the lowest obesity rate, and while not directly related is a rough indication of how long you will live, and how likely you are to die of heart disease. As there is no preventive healthcare that will prevent obesity, that is there is no pill one can take, no bandage to apply to the wound that will fix obesity, going to the doctor or throwing money at the healthcare system will not fix this issue; people simply need to start eating healthily, which is unfortunately a lifestyle choice. In Japan overweight people are taxed and being overweight is heavily regulated, which removes freedoms, but does result in less deaths from these causes, with a noticeably lower heart disease rate. In the U.S. implementing harsh punishments for being fat would not only likely be highly contested but would also be immoral, so instead the focus needs to shift to cultural changes to keep people from overeating. These same sentiments have been echoed by other scientists and researchers, who intuitively and with evidence have rationalized the same thing; the U.S.'s healthcare is good, but the health of the people is still bad, due to the underlying causes of health problems.

To extrapolate beyond this, obesity is more likely to cause heart disease and other health problems, and drug abuse is more likely to cause cancer. Obesity is the leading cause of preventable deaths in the world, and is exacerbated more by cigarette and other forms of drug use. In the United States, obesity is estimated to cause 111,909 to 365,000 deaths per year, while 1 million (7.7%) of deaths in Europe are attributed to excess weight. On average, obesity reduces life expectancy by six to seven years, a BMI of 30–35 kg/m2 reduces life expectancy by two to four years, while severe obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) reduces life expectancy by ten years. Compounded by drug use, obesity is a leading killer, and that's those that are directly caused by it, rather than indirectly caused, such as obesity making naturally occurring heart disease worse. Drug use worsens the impact of obesity, such as by increasing cholesterol build-up and worsening the ability to breathe, and thus directly kills more people than obesity itself. Cigarettes and tobacco kill approximately 480,000 people per year, out of the 2.6 million who die every year or around 20%, and it shortens your life expectancy by about 10 years, with an additional 64,000 overdoses by other drugs, and 88,000 deaths from alcohol. Drugs and obesity also make existing diseases worse, which worsens an unknown number of diseases, but given how frequently drugs are used likely would increase the number more. The number one cause of death in the U.S. is heart disease, followed by cancer, and then heart disease related symptoms, such as nephritic kidney disease or lower respiratory disease. Approximately 600,000 will die per year from heart disease (25%) while another 600,000 (25%) will die from cancer, a large portion of which is directly or indirectly caused by obesity or drug use. The U.S. has among the the highest legal and illegal drug use rate in the world, which contributes heavily to health problems. Particularly cigarettes use is higher, but opiods, cocaine, marijuana, and other drugs are commonly used as well.

All of these factors contribute to heart disease and cancer, and therefore the U.S. has a higher rate of cancer and heart disease than many other countries. One cannot curb drug use by going to the Doctor's office, nor can they stop someone being obese, and in the absence of a magical pill, it simply takes willpower and a guiding hand to avoid these problems. American's problems are more fundamental to the society and culture, as well as environment and genetics, rather than due to the healthcare system itself. We have a 40% higher survival rate for treating these diseases, but have higher cases of being afflicted by these diseases, due to more fundamental underlying conditions. The solution then is to reduce obesity and drug use, rather than to try and change our healthcare system in and of itself.

But I read a study that said...

A common argument about the U.S. healthcare system, is that they read a study that said it was terrible, so how could it be the case that it's actually a good system if other studies show that it actually has high quality? Is one of these studies simply wrong, or where does this discrepancy lie? Unfortunately many of these studies have potential political implications, and thus are important to judge with a critical eye. While there are too many studies in the world to refute, some key one's tend to make the same mistakes or can be misleading in their portrayal, the primary problem with them being that they tend to judge the U.S. healthcare system by the populations overall health or other peripheral issues rather than measure the success of the medicine itself. The primary issue is in judging the health care system erroneously by how many people die of a particular disease as a whole, rather than how well the system is able to treat those diseases once people have them. The term "amenable" healthcare problems applies not only to those that are treatable in hospitals, but also those that are theoretically preventable by lifestyle or environmental changes, such as being avoiding exposure to cigarette exposure or health problems from obesity. As stated before, obesity and drug use is not caused by bad healthcare practices, or malpractice by doctors, but rather by citizens making choices to overeat, or being unable to learn how to lose fat in healthy manners. The same essentially applies to other external factors that are not a reflection of healthcare services themselves. A doctor has to work with what they're given, and can't be held responsible for the choices a patient made during their own lives or problems they incurred. A country that has more car accidents will have more car accident patients in the hospitals, but a higher number of patients or a higher number of diseases is not an indication of how poor the healthcare system is itself. Most studies that claim the U.S. healthcare is in somewhere worse than other countries often suggest that the U.S. has a high death rate from potentially preventable diseases, and therefore by failing to prevent them the healthcare system itself is bad. However, most of these studies will lump diseases such as pancreatic failure or appendix bursting in with heart disease or car accidents, with heart diseases being the bulk of these deaths in their totality and not a reflection of the effectiveness of the medicine itself. These deaths, while many being theoretically "preventable", are not preventable by doctors, and are a reflection of the individual choices or external problems of the individual effected. A better measure of a healthcare system would be to see how well people with a particular disease or condition survive after treatment, rather than how many cases hospitals treat.

Several such studies try to judge the U.S. and global healthcare systems by peripheral healthcare issues rather than the direct objective quality of care of the healthcare system itself, and these studies are are commonly cited by opponents of the U.S.'s system, often incorrectly making the wrong assessment of them. [1][2][3][4] The studies, most of which are largely based on the same concept of amenable (preventable) healthcare deaths, claim the U.S. and other countries fail to prevent potentially treatable, "amenable" diseases at a higher rate than other countries, and therefore that their healthcare system is therefore worse. The primary flaw in this conclusion as a result of the study comes from the fact the term "amenable" applies to both treatable and preventable diseases, as well as an analysis of total mortality figures as opposed to directly looking at hospital treatment effectiveness. Preventable is not the same as treatable, as a disease that can be prevented like heart disease caused by cigarettes and obesity, is not the same as one that can be treated. Preventable in this context just means that it is possible for a person to avoid these lifestyle choices or environments themselves, and not that the hospital has any say over the lifestyle choices of the patients beforehand. The study for example considers avoiding exposure to cigarettes to being amenable, but admits that once the heart disease is present, it isn't treatable. [4] "However, lung cancer is considered preventable only, by means of actions such as reducing or eliminating exposure to cigarette smoking, asbestos and some other occupational factors, as treatment is rarely successful once the disease has arisen." In other words, the quality of care of hospitals is not going to change someone's lifestyle or environment, who might choose to smoke or become obese, which is the obvious fundamental underlying cause to their healthcare problems. The term amenable applies not only to hospital treatment capabilities, but also to the chance of getting a disease that is theoretically preventable outside of hospital care, such as diseases caused or influenced by obesity and drug use, like heart disease, lung disease, kidney disease, and others. The problem with the evaluation of these studies is that obviously it doesn't judge the healthcare system itself directly, and instead looks at total mortality rates, the differences in the figures of which can be due to a number of external factors. The U.S. has the highest survival rate for heart disease, 45% higher than the UK and 20% higher than the next highest country, however due to the fact that the rate of getting heart disease is higher, the total mortality rate for heart disease is higher (with the U.S. having an obesity rate of 38% in comparison for 26% in the UK). Similarly, Australia has a high skin-cancer death rate in comparison to many European countries, however this is due to the higher level of sunlight in Australia causing these higher levels of skin cancer to begin with, and is not a reflection of Australia's hospitals being inept at treating skin cancer. Having more sick people to treat is not an indication of the effectiveness of the healthcare system itself, and ideally the way to judge a healthcare system would be to judge how well they teat each sick person, rather than counting how many sick people they start off with. Heart disease and other diseases are also not perfectly preventable, even if cigarette use and obesity are reduced, and is largely caused by old age, and made worse by drug use or high levels of fat, meaning that no healthcare system, no matter how good, can prevent all heart disease deaths. As heart disease is the leading cause of death followed by cancer, and heart disease related symptoms, considering these to be amenable is only true in the context that the rates can go down with changes to lifestyle, and not anything hospitals themselves can do. Despite this, it is used by a rough baseline to judge the healthcare system by those who cite the study without first understanding the difference between causation and correlation. Copying another country's healthcare system model would not remove how many obese and drug-using people we have in our society, and to suggest otherwise is obviously to ignore the more fundamental problems. [1] "Observed geographic and temporal variations in deaths from selected amenable causes (eg, stroke and heart disease) might be attributed partly differences in risk factor exposure (eg, diet, high BMI, and physical activity) rather than actual differences in access to quality personal health care. Public health programmes and policies might modify these risks in well-functioning health systems, but risk variation can still confound the measurement of personal health-care access and quality."

Another common claim is that approximately 25,000 to 45,000 people die from being uninsured every year in the U.S. This claim has been repeated by several notable politicians, including Bernie Sanders, and is commonly claimed by political proponents of a new healthcare system (often without offering that their alternative program will actually fix the problem). The primary issue with this study is that it is not actually a measure of the U.S.'s total death rate, but is instead an estimate based on approximately 300 deaths from a small pool of 8,000 patients treated in the study. This sample obviously does not represent the entire U.S., and is made from a small sample within the U.S. rather than the U.S. as a whole. In the study, a supposedly 3% higher death rate, extrapolated from an actual difference of a 1% between the figures or 3% in relation, is used as the foundation for the reasoning that 40,000 people might die every year from being uninsured. According to the study, approximately 16.2% of insured people died compared to 17.2% of uninsured people, a difference of 3 actual people in the study, and therefore is somehow "proof" that 40,000 people die across the entire nation if this figure holds true and is not the result of random sampling errors. This 3% difference, which is likely due to random statistical errors given the small sample size of only 300 people being evaluated, is treated as statistically significant in the study, and then used to create a number of 40,000 potential deaths when applied to all 2.6 million deaths in the U.S., making the assumption that this figure is a reliable number and is directly indicative of the entire United States, and not just the people in the study. The study does not prove that uninsured people in the U.S. are actually 3% more likely to die from not having health insurance, but only makes an estimate based on a 3% difference from their sample size, and then extrapolates this to the entire U.S. in order to generate this seemingly large number. Obviously such a small difference could be due to external factors or random statistical errors, but is treated as concrete by the study. Further, as a simple correlation argument, it does not reveal why the individual's actually died, or prove that it was actually a lack of health insurance that killed them (merely proving they did not have health insurance, not that this is why they died). Even if it is true that there is a 3% higher death rate to uninsured people, this could be due to a number of reasons, and simply be peripheral issue, for example with people who choose not to buy health insurance being riskier people in general, and therefore just as likely to die, or that they are more likely to be poor or homeless which shortens people's life expectancies even when good healthcare is provided. Suicidal people or other people intending to self harm often do not pay for health insurance, obviously due to the intent to kill themselves, and would be more likely to die even if they were given health insurance, as would the homeless or those that take other risks. There are many potential factors to explain why the death rate might be 3% higher, and giving these people health insurance may be unlikely to fix their problems (such as being homeless or suicidal). As suicidal people or people in poverty's lives will not change, paying for their health insurance will not fix the underlying cause of their health issues, which should be the primary focus.

Another similar study makes a similar claim, also based on a relativity small 3% difference, that more people being insured has lowered death rates in Massachusetts (based on the Republican Mitt Romney's healthcare plan). However this claim is based on a 3% death rate reduction in the state over more than 10 years, which could simply be due to a slightly lower national death rate across the board rather than from Massachusetts being particularly effective at health care in and of itself (and would prove that the Republican healthcare plan, not the democrat one, would actually be beneficial to society, despite what some politicians such as Bernie Sander's claim). In essence, the death toll dropping has not been verifiabley proven to be from the healthcare program being implemented, and could be due to a number of reasons, such as a general declining death rate across the nation rather than any specific healthcare law in the state itself. Many changes have occurred in the last 10 years, and to suggest the death rate was lowered from any single law is difficult to do, at best, or that it would necessarily be repeatable across the entire country due to the effect it had in one state, which may have simply been lacking in some particular feature. A classic correlation argument, based on an extremely small statistical figure, the study makes the same mistake as the previous one's, however in a different way.

Additional myths and information

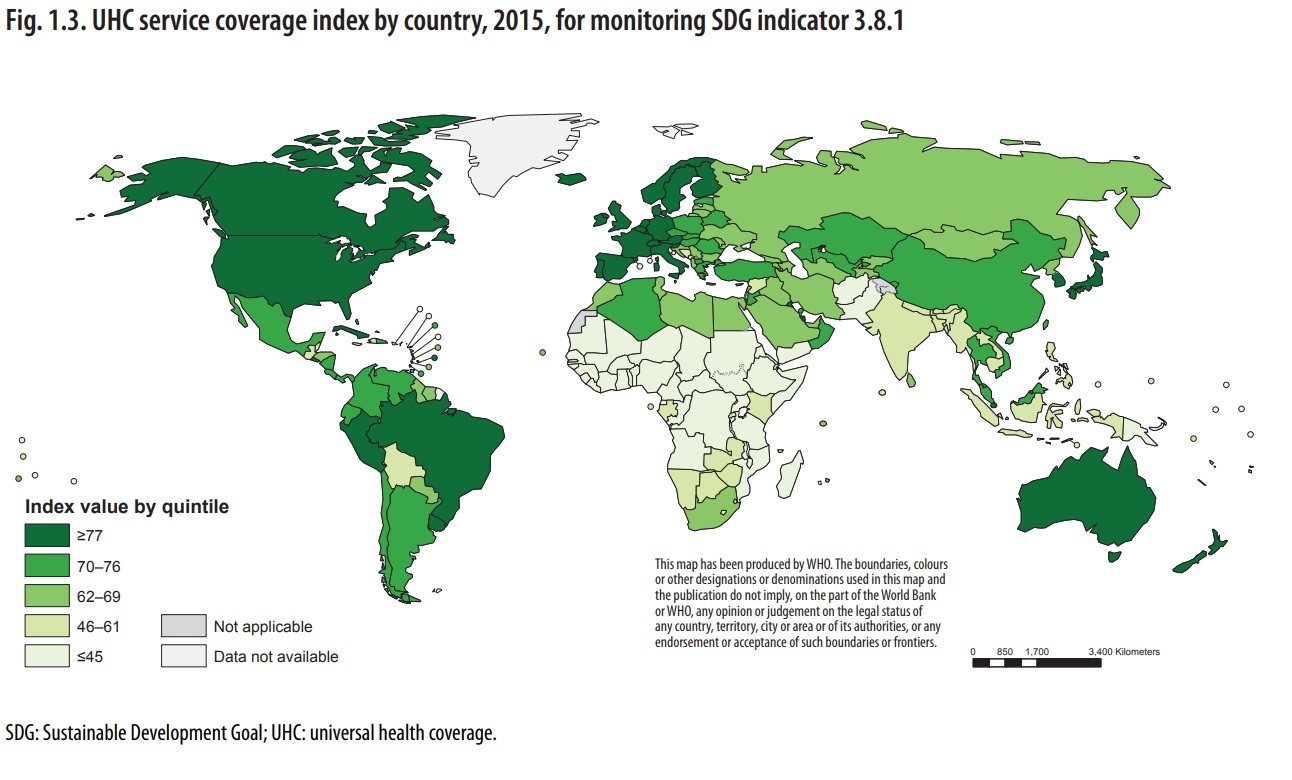

Various additional myths about the U.S. healthcare system persist, such as the idea that uninsured people are substantially more likely to die, or that various political decisions should be undertaken based on this. While ideally these myths would stay out of political discussions sadly they permeate our conversation, and often are prevalent in our daily lives. It is important to address these additional points, and other key issues, as these myths also falsely persuade the opinion's of the American and world public at large. The U.S. for example does have universal health coverage, or universal healthcare, according to the definition by the World Health Organization. [1] Roughly, universal healthcare is defined as less than 10% of the population spending more than 25% of their income on healthcare. This delineates costs on healthcare that are chosen outside of emergency situations, such as cosmetic or preemptive care, and focuses only on a small percentage of the population having financial troubles, as in virtually every society some people will incur medical debt.

"Target 3.8 of SDG 3 – achieving universal health coverage (UHC), including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all – is the key to attaining the entire goal as well as the health-related targets of other SDGs. Target 3.8 has two indicators – 3.8.1 on coverage of essential health services and 3.8.2 on the proportion of a country’s population with catastrophic spending on health, defined as large household expenditure on health as a share of household total consumption or income."

"UHC does not mean that health care is always free of charge, merely that out-of-pocket payments are not so high as to deter people from using services and causing financial hardship. Nor is UHC solely concerned with financing health care. In many poorer countries, lack of physical access to even basic services remains an enormous problem. Health systems have a role to play in achieving progress towards UHC. Health systems strengthening – enhancing financing but also strengthening governance, the organization of the health-care workforce, service delivery, health information systems and the provision of medicines and other health products – is central to progressing towards UHC (Fig. 2)"

In addition, the U.S. already has a voluntary medicare and medicaid system that citizens may opt in to, even if they don't otherwise meet the criteria.